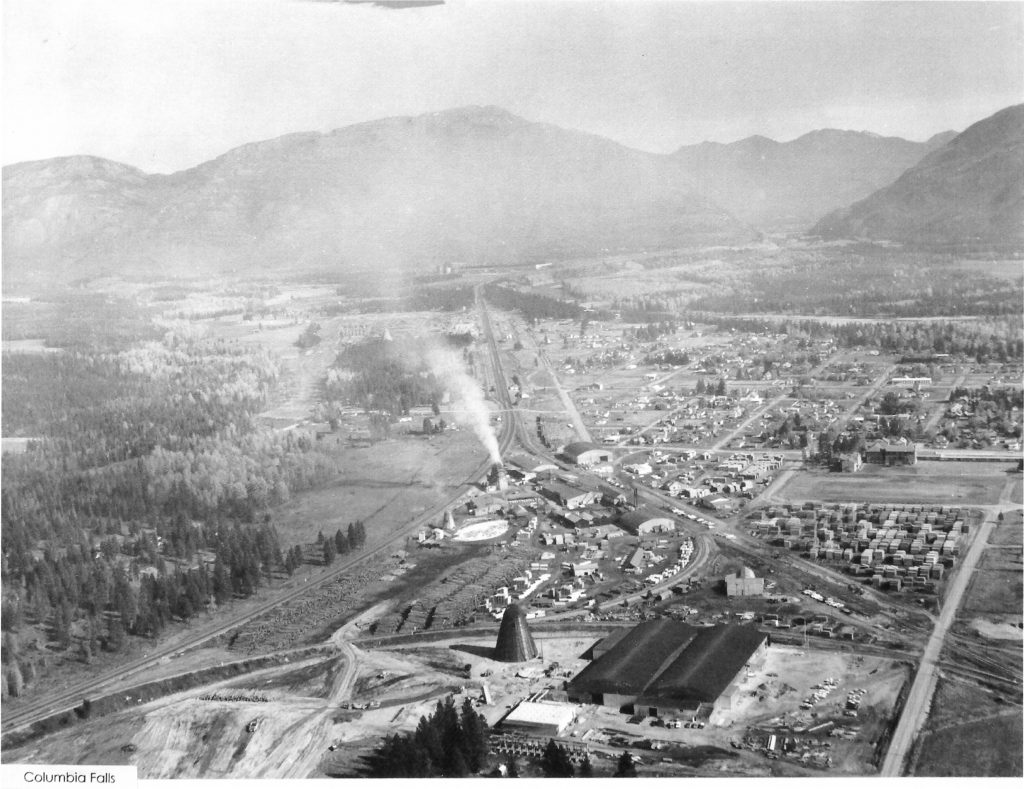

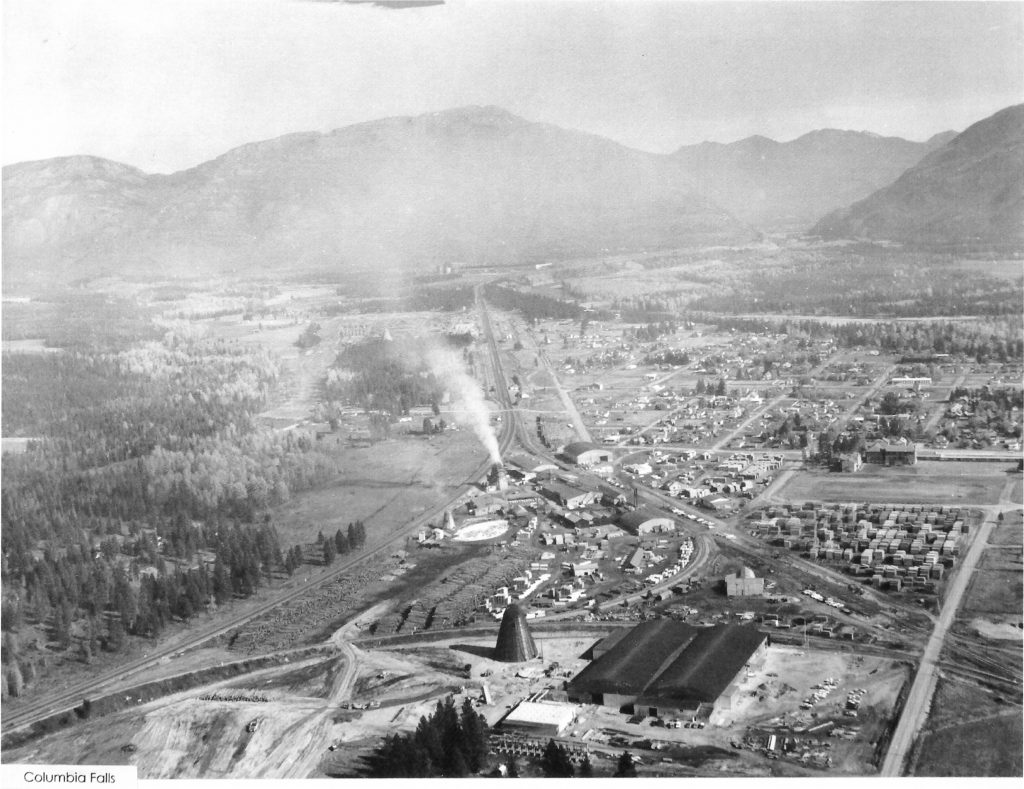

An aerial view looking east toward Bad Rock Canyon with the Plum Creek plywood plant in the immediate foreground, the Plum Creek sawmill right behind, and the town of Columbia Falls after that. The photo was likely taken in the 1960s. Note the inactive tepee burner next to the plywood plant and the two smaller tepee burners next to the sawmill with smoke coming out. No photographer, no date. Photo provided by the Northwest Montana Historical Society, Museum at Central School

By the 1960s, Columbia Falls faced point and nonpoint air pollution sources – timber plants and the aluminum smelter on the one hand, and garbage burning and dusty streets on the other hand. Controlling air pollution was costly for industry, which needed to purchase expensive equipment and keep it maintained, and for government, which had to find a new way to handle garbage, monitor burning across the Flathead Valley and pay for paving streets. For photos and images related to this topic, visit the photo albums on the Facebook site "From Superstar To Superfund."

Chapter 29 – Emission control

The earliest monetary settlements for damages by fluoride pollution took place in Europe in the 19th century and involved superphosphate plants, but the science wasn’t clear for decades. A deadly mist that killed at least 60 people in Belgium in 1930 wasn’t attributed to fluoride until seven years later. The sometimes violent “guerre du fluor” in Switzerland brought international attention to fluoride pollution during the 1970s. Fluoride pollution did not respect international borders, as emissions from aluminum plants in New York crossed into Canada, impacting farms on Cornwall Island.

Chapter 30 – Clearing the air

The worst case of fluoride pollution in U.S. history occurred in Donora, Pa., on Halloween night 1948, when 20 people died but a thousand lives were threatened. Federal air pollution regulations were slow to come, with the Environmental Protection Agency and the Clean Air Act established in 1970. But the individual states were left in charge of establishing and implementing air pollution regulations for the aluminum industry – with advice from the companies – for more two decades.

Chapter 31 – The Pacific Northwest cases

The public was aware of fluoride pollution by Pacific Northwest aluminum smelters since the late 1940s, but important legal challenges involving two plants in Oregon didn’t come until the 1950s and 1960s. The plaintiffs’ legal strategies evolved alongside changing public opinion, and aluminum companies faced mounting costs for new air pollution control equipment. The problem for the industry wasn’t just money – an effective technological solution to pollution didn’t yet exist.

Chapter 32 – Fouling the Big Sky

Industrial air pollution in Butte, Mont., was deadly and pervasive in the late 19th century. After the Anaconda Company gained control over the “Richest Hill on Earth” and moved smelting to the new town of Anaconda, the pollution went with it. The mining company prevailed in court, and Montana’s air pollution laws remained stagnant until the 1960s. That’s when academic activists rose up against a phosphate plant in Garrison and a pulp plant in Missoula. A Clean Air Act was signed into law in 1967, and a decade later the Anaconda Company blamed air pollution regulations for the demise of Montana’s copper industry. The federal government disagreed.

Chapter 33 – Tepee burners and pulp mills

While activists in Missoula called for stricter regulations for an operating pulp mill, activists in Columbia Falls rallied to prevent one from being built. With a Clean Air Act on the books, the state began to implement new air quality standards, and the state’s timber mills was the first industry to be regulated. Meanwhile, the Flathead Valley’s three towns faced increasing pressure to pave their streets. With only two potlines in operation through the first half of the 1960s, emissions from the Anaconda Aluminum Co. plant were not the focus of activists and regulators.

Chapter 34 – Teakettle Mountain

Teakettle Mountain formed the backdrop for the Anaconda Aluminum Co. smelter, and over the years its lack of thick vegetation became a symbol for pollution by the company. The mountain’s history was more complicated than that. By 1969, however, with expansion of the smelter to five potlines, the company faced two undeniable realities – fluoride pollution was killing plant and animal life for miles around the smelter, and public opinion about pollution had changed.

Chapter 35 – Rounding the cusp

By 1969, officials at Glacier National Park and the Flathead National Forest were seeking advice about fluoride pollution from the Anaconda Aluminum Co. smelter, the editor of the local newspaper had taken an about-face on the pollution issue, AAC had paid off a Christmas tree plantation owner, scientific investigations were underway, and public talks on fluoride pollution were receiving mostly positive reactions from local residents. The company’s denials were also softening.

Chapter 36 – Lawyers and scientists

A Kalispell law firm rounded up about two dozen clients to sue the Anaconda Aluminum Co. by 1970, and a class-action lawsuit soon followed. The class-action lawsuit, however, failed to garner local support and was dropped. Local residents were split along traditional lines – jobs versus the environment. As federal investigations of impacts to surrounding plant and animal life continued, the air pollution matter attracted national media attention.

Chapter 37 – The big variance

New state fluoride standards went into effect on June 30, 1973, and the Anaconda Aluminum Co. immediately sought a variance as it continued to look at technological solutions and economic realities. Initial pollution control attempts failed, and the company was given until 1979 to comply with state standards. Meanwhile, investigators continued to accumulate evidence of fluoride pollution in Glacier National Park and the Flathead National Forest.

Chapter 38 – The big conversion

A major problem facing the Anaconda Aluminum Co. smelter was that it had chosen to utilize Soderberg rather than prebake reduction pot designs in 1953. Making outdated Soderberg reduction pots operate more efficiently and with less pollution required converting all 600 pots to Japanese Sumitomo technology. The company also replaced its wet scrubbers with Alcoa dry scrubbers.

Chapter 39 – Litigation and the end game

The U.S. Justice Department sued the Anaconda Aluminum Co. on behalf of Glacier National Park and the Flathead National Forest in 1978. The lawsuit was settled in 1980 after investigators found plant life around the plant much improved and the Anaconda Company offered a land exchange. But there was a back story to the settlement.