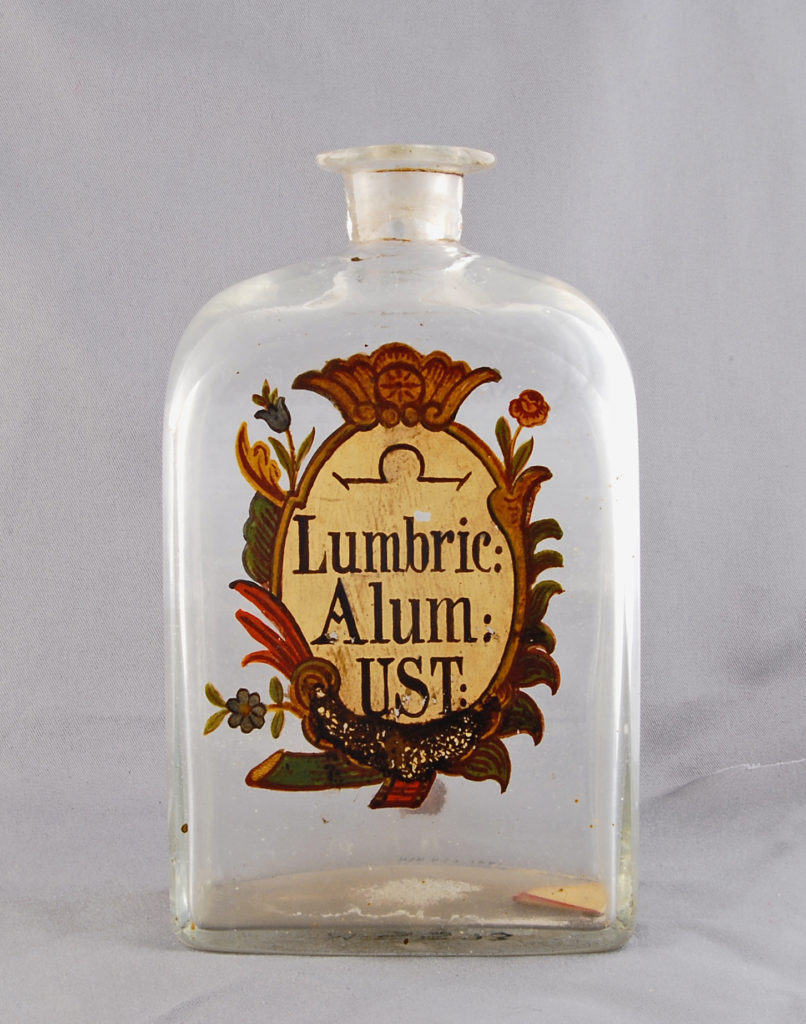

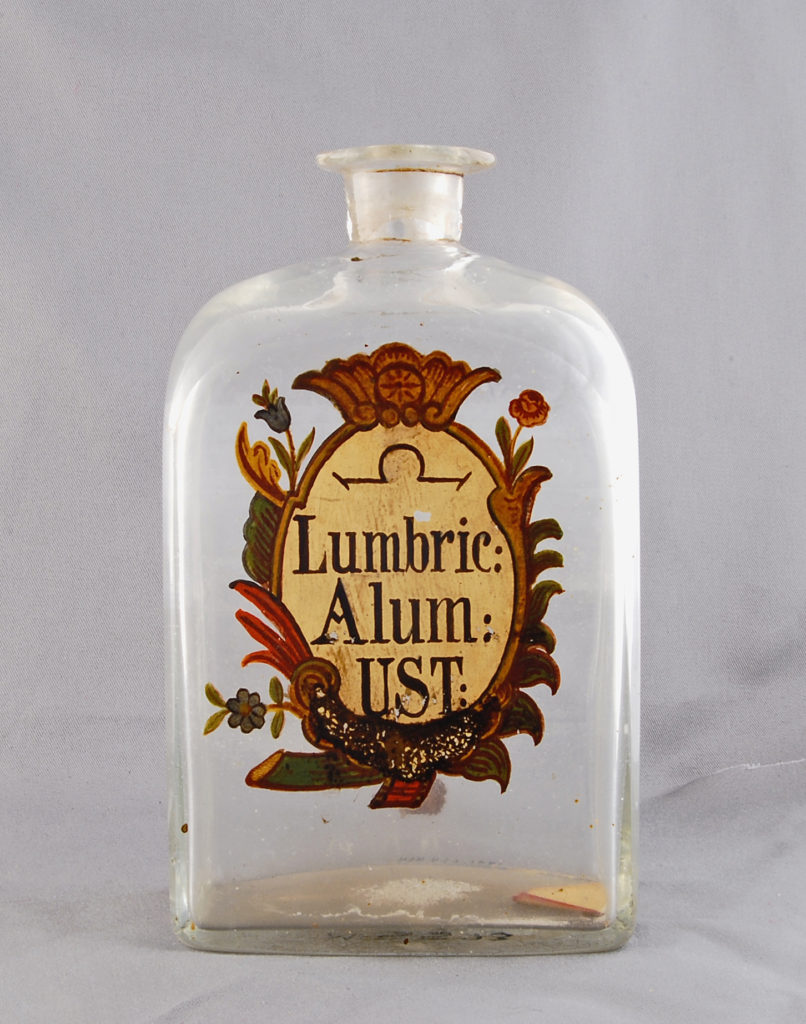

This square glass bottle is labeled Lumbric Alum UST with the alchemical symbol for Spirits. Lumbricor is dried and pounded earthworms, alum is potassium aluminum sulfate, and ustum is Latin for heated. The solution was often used as an emetic, astringent, or diuretic. Photo from the National Museum of American History, Kenneth E. Behring Center

Aluminum is commonly found in the Earth’s crust, making up 8% of the lithosphere by weight, but unlike gold and copper it is never found in metallic form as nuggets or in ores that were smelted by ancient civilizations. The hidden metal was bound up in compounds that ranged from gems to clays. For photos and images related to this topic, visit the photo albums on the Facebook site "From Superstar To Superfund."

Chapter 1 – Ubiquity and antiquity

Aluminum compounds were used thousands of years ago to make fine porcelain, medicine and dyes, but alchemists and early chemists sought the missing element in these compounds. By the middle of the 19th century, aluminum was being produced in small quantities and was valued as a precious metal.

Chapter 2 – Synchronous discovery

In 1886, an American in Ohio and a Frenchman in Paris discovered the reduction process still used today to produce aluminum metal. But the process depended upon other discoveries – bauxite in France, cryolite in Greenland, electrical power generation and an economic process for refining bauxite into alumina.

Chapter 3 – The young entrepreneurs

A group of businessmen in the steel town of Pittsburgh made a leap of faith during the second industrial revolution and backed the new aluminum reduction process discovered by Charles Martin Hall. In seven years, the new company evolved from a pilot plant in Pittsburgh to industrial-sized production using power from Niagara Falls. The company changed its name to Alcoa in 1907.

Chapter 4 – Patent wars and vertical integration

It took about two decades for Alcoa to completely secure patent rights to the modern aluminum reduction process, but during that time the company moved toward vertical integration. The company acquired rights to bauxite reserves in the U.S. and South America but delayed implementing the Bayer process for refining alumina. It invested in hydroelectric projects in Quebec, Tennessee and North Carolina, and it established research facilities to improve production of aluminum metal and fabrication of shaped products.

Chapter 5 – Creating aluminum markets

While aluminum had a good strength-to-weight ratio and conducted electricity well, early users found working the new metal to be difficult. The invention of the Duralumin alloy in 1908 opened the door to use of aluminum in aircraft. In the first decades of the 20th century, aluminum products appeared as cooking utensils, packaging foil, electrical transmission cable, automobile parts, windows and doors, furniture and military applications.

Chapter 6 – Building a global industry

Paul Louis-Toussaint Heroult, the co-discoverer of the modern aluminum reduction method, went to Switzerland to promote aluminum production, the origin of Alusuisse. The early French companies eventually merged into Pechiney. The British Aluminium Company was organized in the last years of the 19th century and soon invested in Norwegian hydroelectric sites. Many major aluminum-producing nations emerged in the last half of the 20th century – Australia, Norway, India, the Middle East and the juggernaut of China.

Chapter 7 – Surviving “Satan’s Church”

Aluminum reduction pots emit poisonous fumes and operate 24 hours a day and seven days a week. Hazards to workers from fluoride, polycyclical aromatic hydrocarbons and other gaseous or particulate emissions have been known since the late 19th century, but much of the scientific investigation of these hazards didn’t take place until after 1970.

Chapter 8 – Organizing the potmen

The aluminum industry differs from many other economic activities in that labor costs account for a smaller portion of overall production expenses, but workers must be reliable, skilled and trained. As a result, U.S. aluminum smelter workers tended to be paid higher than workers in other heavy industries, even if it took federal New Deal legislation to get them organized across the U.S.